Bucharestian’s note: the text below is a translation of an eye witness’ account with the author’s consent. While putting it in English, I have tried to keep everything as close to the original as I could. Information-wise, the text has been subject to no changes, additions or deletions. I have only provided notes - always distinctly, in brackets - in order to clarify locations, specific situations or nicknames.

The story of a 22 year old eye witness

Bucharest - December 21-24, 1989

Nature and weather were on our side, giving us the warmth of springtime, even though the nights of late were - or rather appeared to us due to fatigue - chilly. We gave up even on the illusion of warming our frozen hands and bodies against bonfires when we were told that mercenaries had mined the whole building of the former Central Committee (n. the Central Committee of the Communist Party, referred to as the C.C. from here on). We all turned off those smoky fires and went on shouting: 'We are not going to leave!' and 'The Army is with us!'. Many such lines were created and we, armed only with clenched fists and a fierce will not to give up, with an unbelievable brotherhood and care for those around us, went on shouting so as to encourage the young soldiers in their tanks, so as to boost up their and our morale, as we were all so unprepared for something like this.

For who would have thought that history would turn that way? Who would have thought that we had been paying so many thousands of terrorists for so many years? God, I haven’t got words enough to describe everything that went on, everything that still does. Why had it to be Romania - again - that horrendous u-n-i-q-u-e place in the whole world, for no other nation saw so many deaths, no other people saw so much destruction and material, spiritual loss, no other former leader was less dignified, had less logic and common sense or caring for his people as the one I saw on TV yesterday. Two Middle Age boors (n. Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu), the son and daughter of a Nero, Caligula or Hitler displaying an extraordinary effrontery and madness. Pity they met their death so easily and quickly, pity they did not live to know humiliation, shortages, pity they did not live for once what a whole nation lived for decades. Pity we all accepted being so cyclically terrorized by these two madmen for so many years, for it was plain clear that especially he did not realize what was actually happening. They were the two main sick characters, but I wonder how many other sick characters lived around them and among ourselves…

Thursday, December 21, 1989

Only 10 days to go till the end of this so bad a year. When will Romanians wake up, when will these 22-23 million people come to realize the power lying in their number? It is a beautiful, rather warm and springish day. In fact, it has been like that for a few days already and I am dressed rather lightly, wearing shoes, light trousers, a shirt and a sweater, a coat. I do not have the handbag with me. Lately I have been disgusted by everything, I have no longer cared about the way I look, so I am carrying this small red backpack. I am still at work (n. in the building of the Law School, West of the centre) and I should go straight back home, mother is waiting for me, we have some errands to do together. For some reason I am not aware of, we are all stranded in the building, nobody is allowed in, so I go down, the official paper in my hand for the lady there. Even before the Congress (n. the 14th Congress of the Communist Party, November 20-24, 1989) we got used to this new regulation, with this useless guard spending one's energy upon entering the Rectorate. It was maybe that the events in Banat (n. referring to the city of Timișoara in SW Romania, where the first anti-Ceaușescu riots burst on December 16, 1989) have not cooled down and the government keeps things under a close scrutiny, so that the capital city does not get the riot bug. All of a sudden, a rather weak thought comes to my mind: what about a stroll across town, just for a look? It appears more like a foolish thing; what is there to see but the same filth, the same meagre, grim faces, the same eyes dying out of this hopeless existence? There is however something drawing me, so that I start walking towards Izvor subway station, wishing to go to the Civic Centre and the shops there; there I might find what I want for my mountain hiking trips: solid fuel.

I go out of the building, everything appears normal, so quiet that I almost hate it. I am terribly hungry, but there is something keeping me from going home. I do not know what it is, what it was, even now, as I write these lines days later, but I am sure that many young people followed the same thought, the same weak line of smoke, to the place where they were needed, where they had to be. Passing by the great marble-covered building (n. the House of the People, currently known as the Palace of the Parliament), I start walking up the shop-lined avenue. Suddenly, there is this helicopter passing. It does not stir my interest much. I then see it, but to no great interest either. It is weird, but I do not find it out of place over Bucharest. I take it as part of the precautions taken by the administration to prevent Bucharestians from walking in groups. It is a war helicopter flying at a low altitude. It is for the first time that I see a helicopter, but there is no doubt it belongs to the army: it is painted in khaki and bears a red-yellow-blue target-shape logo. During the next 15 minutes I see 5-6 of them. I go on towards the Piața Unirii, without any thought. I feel a little restless and anxious, as if an unseen magnet is drawing me. I am intrigued. All shops are already closed and their attendants are walking in the opposite direction and chatting while doing so. Schedules in shop windows are simply covered with a white paper reading 'closed'. I do not understand why it is so, as they should be open until 5:30 PM. What has happened? Is there something going on? But there is no time to think about it, as I approach the Piața Unirii and I see ever more people.

Three soldiers and their superior stand by a corner; they all hold guns. I feel this urge to spit on them, right at their feet, but I instead keep going. It is rather weird to see so many people standing together. For there are people filling all of the Piața Unirii. Then there are the whistles. What has happened? Have they arrested someone? A helicopter. Now I can clearly hear it from the front: whistling and booing. I hurry up and, totally unusual for me, I go towards the crowd. People in 4-5 groups of 30-50 persons threateningly raise their fists as a helicopter passes by. I then get it, I hear what people are talking about. I am… I do not know, it feels like a coma or a bewildered, still, shy joy. People say they do not care if those in helicopters film them and there are going to be be consequences as there were in 1987 in Brașov (n. riots that took place on November 14-15, 1987, originating in Brașov's Steagul Roșu truck plant and reprimanded by the regime). This woman, a young brunette, talks about the last news that went through Radio Voice of America, about the current events in Timișoara. She came here on purpose, as she saw from her window people gathering around. There is talk about ever more cities where people took it to the streets in protest: Arad, Satu Mare, Sibiu, Cluj, Iași, Constanța… I then find myself talking, very odd for myself. Then this man says we should stay up all night, for only this way we can make things happen. Many people leave, they think about their families, children. They come and go. They are afraid, for we shall never forget we have lived through the Empire of Fear, Fear has become an inner part of us. I am determined to stay. There is a lot of people. Helicopters come and go. It is almost 5 PM and the twilight is near.

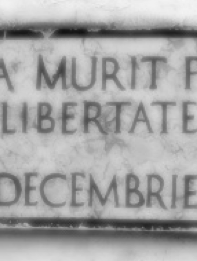

Someone says we should go to the Palace (n. the former Royal Palace, hosting the National Art Gallery at the time), in front of the C.C.: 'let us have our voice heard there!'. And so we all start, even though scattered, towards the Intercontinental (n. Intercontinental Hotel, located off University Square, from where many foreign correspondents were to follow the events in December 1989 and up to June 1990). More and more people follow suit. Those walking opposite us are advised to join us: 'Join us!', we in the front rows start shouting. It is all an act of despair, for if the others do not join us, if we do not get a big number of people, we do not stand a chance. Without exaggeration, starting with that moment, I no longer feel fear; I feel fear dying in me, as the courage of my young age takes control and the presence of all those around me gives fear a final, lethal blow. We all become aware that each and every one of us has a vital importance for the group. We are mostly young, under 30 years old. As we pass by the Bărăție (n. Bărăția Church), we see thick lines of people of all ages standing on the sidewalk, frantically clapping their hands. 'Join us!', we look at them, grab some by the hand or collar and we pull them towards the middle of the road. There is a boundless enthusiasm. Upon reaching the wide University Square, I am shocked by what I see: this huge compact crowd, thousands upon thousands of people stretching all the way to Dalles Hall (n. past the Northern tip of the square). I haven't expected this. I started down at the Nation Square not thinking there were, there could ever be groups of people in Bucharest (n. in December 1989 it was forbidden for people to walk in groups at night), and upon seeing this heterogeneous crowd of people I get the shivers. The step has been made! Here in the capital city, we have eventually awakened. And we are all aware now that the whole world knows of our solidarity, understands and will help us. The time has come for Romania to explode, the time when people, shaken by the bloody retaliation of the riots in Timișoara, unbutton their shirts and are ready to die if that is the only way of getting their Freedom.

That day and night, of December 21, 1989 is to be the most frightening, beautiful, dramatic, the most everything of them all, as we do not know what is going to happen. We have gone out in the streets committed not to give in, with bare hands, without even stones or sticks. Our purpose is to have a peaceful meeting, without any trace of violence, without blood or victims. But it isn't to be so. For Romanians living in Romania have once again to be unique, for nowhere else so many people are to die, nowhere else children are to be shot at, nowhere else and never. The man the resignation of which we are all asking for has been unique in his cynicism, bestiality, madness, cruelty, and we are - in our turn - unique, too. I have never thought that such a solidarity can ever grow in this country, among these people. Someone has got some white candles and spreads them around, someone else has got bread and salami, a piece of pastry. People living nearby come carrying jugs of water, hot tea. We all ask those around us whether they want a sip of water or some bread. Foreign guests up in the Intercontinental look at us and take pictures of us, so that we are sure that people the world over will know about us. I look around me, not a single person I know. I get to the front of the crowd. Not much farther, facing us, I see something terrible: this line of children, young men right out of the compulsory military service, wearing white Miliția helmets, holding white shields and rubber sticks, form a white fence in front of a great crowd of khaki uniforms. Hundreds and thousands of soldiers and officers. There we are, two enemy armies: the government army and the people army. We cannot go on towards the Piața Palatului (n. the Royal Palace Square, referred to as the Palace Square from here on). There are many, so many of us, there is not a single free spot. People take out a table and place it in front of the Dunărea confectionery shop and this young woman goes on top, then more people join her, standing, then shouting. There is no way for us to hear what they say. A form of communication is then created: pieces of paper with notes are passed on from the front: 'We are not going home!', 'Those leaving are cowards!', 'Those leaving are not Romanian!', 'Strike tomorrow!'. Of what they say up there we can only get fragments we try to put together in a logical form. We need to put together a list of claims because, in the end of the day, everyone knows what they want, but as everything is so spontaneous, we are all somehow dazzled, confused, shaken. I suddenly remember to look for a public phone and call home. Mother is despaired and she scolds me. I hang up and get back to the crowd. I do not care what mother says, caring would mean going straight home and if everyone else listened to their families' calls and threats, nothing would happen. To die fighting for survival or to die letting a crazy regime kill you while having you starve in all possible ways???

We then proceed by sitting down or kneeling down on the pavement. This way, the army forces can clearly appreciate the number of people it is all about. But slowly people can no longer keep their temper, so every time a helicopter passes over, we all stand up and shout, among a chorus of booing and whistling: 'We're not leaving, we're not leaving!'. It is getting dark. A first amphibious armoured fighting vehicle runs in quite high speed across the compact crowd. I can hear shouts and groans. Many people and children have been crushed. Two more such vehicles follow suit in even higher speed, cutting through the crowd and making more victims. They are coming from the Nation Square, people are standing all over, so that we, those located in front of the National Theatre and the Intercontinental cannot see and can hardly assess the direction of these vehicles. It is only that quite late, right before it strikes we notice it and start running away from it. Those not able to run or those caught in between crowds fall under the wheels. Two armored Tatra vehicles follow in full, crazy speed. We keep on running. One of the latter slows down for some reason and the one following it takes a sudden left turn, crushing even more people. Protesters quickly re-group and start running wildly towards the white fence created by the shield bearers.

It is 05:45 PM when the first gunshots are heard; I know for sure because, while shouting, I try to write down the flow, keeping track of time. They then start firing the sinister tank cannons; even though the cannons are pointed upwards, they are still sinister an image. Flares go up towards the stars, profaning the sky above. We all back up, crawl, look for shelter behind cars and trees. A young woman is hit by a bullet in her neck. A few people get her. It is unbelievable, but they have started shooting! And they are not shooting only upwards! People die, people get wounded. I can see them carried away probably towards the Colțea Hospital nearby. Two ambulances then show up. Finally, the shooting comes to a halt. The army has meanwhile considerably advanced. The crowd regroups again. Our number is ever greater. People shout: 'Down with Ceaușescu', 'Ceaușescu, be a gentleman, do like Honecker!'. The decision not to give in is overwhelming. 'We fight, we die, but we shall be free!', 'Down with the murderer!', 'Timișoara!'. People are startled, we are all intrigued, but we still try to act peacefully. At about 6 PM they start the water cannons. I run away, we are all terrified, but there is no fear of death, as a certain stubbornness can be seen on everyone's faces. I might be wrong, words betray me every now and then, I don't know, but there is this sense of satisfaction in the air, a certain satisfaction of the crowd facing the retaliation forces. How come? Satisfaction because we are all one, because we have come in such great a number, because the idea not to give in has got into our bones, because we can regroup with an unthought of speed, because we behave like small children that do not have the faintest idea what fear stands for. We have just been shot at and we should be afraid for our lives, but most of us - so many of us, firmly standing there - had rather die than go back to the situation hours and days before, than live again the way we have done until now. Even though many of us do not think about it or do not know it now, Tacit's words have come back to life: 'It is better to die standing than live kneeling'.

So I go running towards the National Theatre. Water coming from the cannons has not reached me. Two-three vehicles with just as many canons pointed in three different directions like long cancer-stricken arms, manage to fill up with water and entirely clear Magheru Avenue (n. Nicolae Bălcescu Avenue). What an unforgettable image, like so many others! But the vehicles go on. The foam-filled street remains deserted for a few minutes. There is just too much water and foam. But people start shouting ever more frantically: 'Step down! The people doesn't want you!'. We slowly gather in the middle of the square with ever fewer people standing on the sides. There are candles burning in our hands. We go shouting like an answer, like a free reply to what we, the people, were accused of the night before: 'We are not Fascists!'. We draw near the soldiers and, looking them in the eyes, go on: 'Soldiers, do not forget we are brothers!', 'We are the people!' and, pointing to them: 'And you are the people!', 'Olé, Olé, Olé! Where is Ceaușescu?', 'Olé, Olé, Olé! Ceaușescu is gone!'. It suffices that someone comes with a new line and it spreads around, being carried away by thousands of chests that join in a single voice raising itself to the clear, star-filled sky; the cannon flares have died out and now there are only the stars up there, those fire-flies looking down at us and encouraging us, but not being able to help us. However it is them that stand there as our witnesses as virtual eyes of the Universe. We are committed to stand there until we get what we want. 'Ceaușescu and his clique, enemies of the people!'.

At about 6:30 PM a bed sheet is tied up to a light pole. There is written on it, in red paint: 'Down with the tyrants! Down with Ceaușescu!'. We go squatting and go on ceaselessly shouting. Timișoara had us started, the very thought at the inhuman retaliation gives us the creeps, but also the kick to go on. Most of us have probably listened on the Voice of America Radio the recording from that city, with that thrilling 'noise'. I listened to that recording three times and cried just as many times. 'Yesterday in Timișoara, today all over the country!'. New calls are made: 'Do not work tomorrow!', 'General strike!', words written on sheets and on the walls of the Intercontinental. 'Ceaușescu, do not forget, your doom day has come!' or 'We revenge Brașov!'. I get near the white shield fence to the right, towards the USA Embassy. I get a close look at those children in uniforms, none of them is over 20-22! They are ashamed to look at us and when one of them actually does, you feel pity for him, it is as if they are crying; but, on the other hand, their passivity is intriguing. We go on trying to explain and convince them, but to no avail that evening and night. Everything has to start with their superiors, they are afraid. They just look at each other with impotent eyes. One of them asks for a cigarette and someone gives him an already lit one. People ask them: 'We are the people! Who are you?', talk to them: 'You are starving too!', 'We too were soldiers, but never shot at our brothers!'. At a certain moment, a second line of uniform-wearing military is formed and stands behind the white shield-bearers, challenging the latter, guns in their hands, not to give in to the protesters; I no longer remember the colour of their uniforms. There are horrible moments, I do not know what the soldiers feel, but we all know that without the army on our side we do not stand a chance. We go on cheering each other, encouraging each other, shouting as loudly as we can, up to the heavens and the army: 'You do not have enough bullets for us all!', 'We shall not forget the bloodshed!'.

I go walking through the crowd, I would so much like to meet someone I know. I am searching for someone, but it is that only later on I realize that I am actually looking for someone to talk to. I am stunned, I look all over, seeing those smiling, young girls ready to die if needed. It is obvious we are not going to give in at all costs. At a certain moment I get this idea to write down what people are shouting. Three times people stop and ask me about the reason behind my doing so. However I have no fear of those boys that, with their firm, suspecting faces, ask me why I do this and want to see what I write. And I do believe that it is strange to see, in the middle of that stirred and preoccupied crowd, a young woman carrying a small backpack walking around and writing something. I get their suspicion and want to know in my turn what they are thinking, what harm I can do with my notes. I do not know what is about to happen, the way the events are to unfold, I simply have to think about what can go wrong, of a retaliation of our protests. Yes, I have got used for the last 20 years to consider the worst scenario first, that is why I want to write it all down, so that these notes and the truth in them can be spread and known by all my friends in Europe and farther on. I have no idea how I can actually pass on the message if we get defeated; due to a letter of 'inadequate contents' that was found out by the authorities, I have already had the chance to get in direct contact with 'their' mentality and to feel like a chess piece one moves at will. But this is another story and as far as that matter is concerned, I can only hope to get back to my original job.

Back in the square, calls come and go incessantly, unbelievable words and rhymes go towards the heavens. 'The people does not want you! Neither you, nor her!' (n. Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu), 'You criminal!', 'Child murderer!', 'At the 14th Congress we did not vote for you!' or 'Ceaușescu is to die, Romania is to flourish!', 'Christmas without him!'. I do not know, it is all extraordinary! We sometimes turn our eyes and voices towards the balconies and windows of the hotel (n. the Intercontinental) that rules over the dark square; we know that we are looked at, listened to, shot pictures and films at from over there, so we shout with a mixture of enthusiasm and despair: 'Europe is with us!', 'We are not leaving, we are not leaving, there are more of us coming!', 'The Army is with us!' - even though it still fails to do so. People ask for free elections, keep on insisting that nobody leaves and that a general strike is set for the following day. The news spreads that 2000 workers at the 23 August Plant are coming to join us and we immediately cheer with a big 'Hurray!!!'. Some of those in the first row try to approach a few soldiers, there is an impressive and peaceful effort of showing them we are right with our demands. We all go on: 'You do not have bullets enough for us all!', 'Whom do you support? Stand on our side!', 'The army in Timișoara joined the people's will!'.

I do not know and I am sorry if I repeat myself, if I say the same thing over and over again, if I take too much of the reader's time without saying anything new. But what I write here is not a novel, at that moment down in the square everything looked and felt still, we were all standing still, well, we were in a continuous movement, but we were actually standing still. There were thousands of us, so stubborn and decided to win and, for the moment, for the beginning, our presence in such a large number, our panting, our candles and everything we kept on shouting, our dialogues - or rather monologues - with the shield-bearers, all these made for the only form of showing our revolt, for we did not know, we did not think, we did not anticipate what would follow one, two or more days later on. It is obvious we could not, for everything was overwhelming…

In the square, we go on shouting: 'The bloodshed will not be forgotten!', 'We want Ceaușescu and his wife out of Romania!', 'Romania, do not forget: today is your birthday!', 'We ask for a new government!', 'Down with the dynasty, it has ruined the country!', 'Down with the shoemaker!' (n. reference to Nicolae Ceaușescu, which came from a shoemaker's family), 'Down with the illiterate!' (n. reference to Elena Ceaușescu, a self-entitled academician of very weak educational background), 'We are not leaving until we see them in court!', 'We fight, we fight and here we stay!', 'The new year without the tyrant!'. This is not a mere line-up of things people call and shout to heavens, but these are rather words born out of hatred, hope, despair, desire. Who would have thought we were going to live the day to call things like that in a loud voice?! It is almost unbelievable. 'Now or never!', 'Bucharest, Bucharest, you love freedom!'. Ceaușescu's arrest is loudly demanded. 'Ceaușescu, export merchandise!'. At about 7:30 PM people start a hora dance. They join hands and dance on (n. Vasile) Alecsandri's lyrics. The most moving moment occurs when we sing aloud (n. Andrei) Mureșanu's revolutionary march, 'Deșteaptă-te, române!' (En. 'Awaken, Romanian!'), with lyrics fitting well some 141 years before, but also at this very moment! There are more shouts: 'We're waiting for the resignation!', as our courage and self-possessed actions get ever stronger, to astonishing levels. 'Even if you shoot us, you cannot take our freedom!', 'Let us fight tonight and save our future!', 'Timișoara in blood, Romania in tears!', 'Ceaușescu and his wife, we no longer want them in Romania!'. Timișoara is getting back on our lips every now and then, in a persistent and thrilling manner. We again and again approach the army: 'You are defending a dog!', we beg the soldiers: 'Soldiers, join us!', we ask: 'Let the fire squad leave!'.

At 08:15 PM they start shooting again. It is terrifying. The water canons are again pointed at us. The water is ice cold, exactly like the one we get down the hot water pipes in the middle of winter. I run away - well, this is just a matter of speech, as there is nowhere to run, there is a real crisis of space. I go together with the crowd to the sides of the square. I am pushed in the big windows of the Société Générale offices. But even if it was chilly and our wet clothes turned to ice, we would not go away. We want to have 'The New Year without the ox!', we want him 'In court!', 'Back to Doftana!' (n. a prison where Nicolae Ceaușescu was allegedly imprisoned during his youth). By 08:30 PM a group of protesters join us, coming from the USA Embassy, there were the soldiers used to be. I have not noticed them retreating, as I went down in the subway station to make a phone call. Those having one, share a coin with those in the need; calls are rather short, some call their friends and colleagues to ask them to come to the University Square, others call their parents to reassure them by saying they will stay overnight with some friends. It is all so moving. Finally, a really popular gathering. As I come out of the subway station, someone has brought a loudspeaker and a list of claims is presented. A man from Timișoara shares his experience with the protest there. Then a series of announcements are made, to be proven fake afterwards. For instance, a woman's voice announces that it has been officially stated that the Romanian Army joined the protest. As a consequence, when not much later a few more tanks show up in the square, people rush to them and try to get on top of them, to be rejected at gunpoint. Another fake announcement is then made: the Ceaușescus have left the country on board of a helicopter, destination France. Something terrible happens then and people suddenly panic: several people form the crowd have been arrested and pushed in Securitate (n. the Communist secret service) vans. Then the names of several personalities are chanted: Doina Cornea, Dan Petrescu, Mircea Dinescu, King Mihai I. Then: 'Down with the red fascist!'. By 09:45 PM a former political inmate at Aiud talks to the crowd. Candles burn on. 'On and on / Ceaușescu will be down!'.

At around 10:15 PM there is brought an empty truck with the purpose of creating a barricade. A barricade was attempted before, at about 5 - 6 PM, by employing the tables and chairs on the terrace of Dunărea confectionery shop, but it was aborted as there were many demonstrators caught up between the barricade and the army. A man gets on top of the truck and starts talking through the loudspeaker. A father asks help for his three boys that were snatched by Securitate officers earlier; a young man says the same thing about his father, arrested at more or less the same time. Another truck comes around. A woman picks up the loudspeaker and addresses the army, kneeling and crying, begging the soldiers to join the population; her son was killed in the streets of Timișoara during the protest there. People then rush to a supply truck parked in front of Pescarul Restaurant, hungry and thirsty. We are all hungry and thirsty, but this is not the reason for our spending the night here.

At 11:00 PM there is a call to silence to everyone around, so that an army representative can have an important statement. There is no silence however and the statement cannot be made. By 11:10 PM, bullets and tank canons can be heard once again. Then the first teargas grenades are employed. I am next to this flower shop and I find it next to impossible to run. The effect is immediate, as I am very close to the place where the grenades fell. With great difficulty I try to walk away from the spot that unbearable, burning mist and that carbide stench come from. I can no longer see due to the tears in my eyes, my throat aches down to the lungs, I am walking like a robot. I do not know how I get next to the Faculty of Architecture, but I do. Someone takes me by the hand and helps me sit down, someone else gives me a wet handkerchief. I am eventually relieved, as the effect is rather short-lived, I believe around 5 minutes. It is a bit more difficult with the eyes, but I can eventually see again and I get back to the avenue. They throw tear gas grenades again, but this time I am farther from where they fall. There is a thick mist, an opaque layer, so that one can no longer see the Intercontinental from across the street.

People stubbornly regroup. 'Bucharest, Bucharest, you love freedom!'. I can now see the messages written on the walls of the University and of the confectionery shop. I light a few extinguished candles. It is terrible there already are victims in this University Square. There is intense shooting, the pavement under our feet and the sky above shake as they go on shooting. The barricade truck catches fire, then a small mail van is pushed into the fire by a few men, probably not some of us. The fire is shedding a sinister campfire glow, with black smoke clouds going up, with thousands of sparks breaking away and filling the air. I once again get to the middle of the avenue, but we cannot regroup as before. They are continuously shooting at us. The firing goes on for a long time, the barricade fire spreads on; I run towards the National Theatre. People are running. There is more shooting at us. The earth is trembling. More shooting. The avenue is clear of people now. Defiant and cynic, tanks and fire squad trucks are now moving back and forth across the square. They go on shooting at us. The crowd is dispersed, we can no longer hope to form a compact crowd like before. I am not familiar with either warfare or weaponry, but I can hear some terrifying blasts and I feel the urge to cover my ears. God, what an apocalyptical noise!

I do not know, I am maybe wrong, but I think that night was the most horrible of them all, worse than those that were to follow: we did not know what attitude the army would adopt, we were unarmed, we only relied on the assumption that they could not arrest or kill us all, as well as on the fact that the international community was aware of what was going on in Romania… I obviously did not know what the others thought, but I think our thoughts defied all barriers and joined in an impulse that explained our being there. There.

There are ever fewer people around me. Then I am alone. I do not know where to go, there is no reason to stay. The Intercontinental is surrounded by the army. In the dark I can see this group of soldiers with rubber sticks running towards the (National) theatre. Together with others I run and we get to the Operetta (n. hosted at the time in a building now part of the National Theatre). There is only a handful of us. A shot young man is carried away past us. We can see no other groups. Down some narrow streets to the back we meet another, larger group. We are at a crossroads, next to the Batiștei Polyclinic and the Cultural Centre of the Democratic Republic of Germany. We all then get in front of the USA Embassy, there are some 50-80 of us, most of us young. We call the name of President Bush and ask for help. There is an act of despair, a call that cannot realistically have an immediate effect in the direction desired by us at that very moment. A row of shield-bearers has already formed to our left. From inside the embassy, from a window, a man waves at us, then a woman follows suit. They light a candle, then they wave again from the next window. All of a sudden some in our group start running to the right, shouting something. I automatically follow them, convinced that the others will come after us. What is going on? I go on and, turning my head, I can see those remaining there caught up between two rows of soldiers, the one to the left and a new one created right after my leaving the spot; the new row is double, with some soldiers facing the remaining group and others facing the 10 of us. What is to happen to the about 50 or more persons caught up in front of the embassy? I am yet to learn that arrests were conducted and 8 young men were shot in the head.

There are 10 of us left, three girls and seven boys. We go on, walking those already deserted streets, we get to the Embassy of Hungary, where the guards want to find out what has happened downtown. We all stay for about 20 minutes in a small park and then we decide to go home. As I live in Militari (n. a remote district from the centre in W Bucharest) and the others are in groups of friends, I do not know what to do. Five go, five remain and then, at a crossroads, two boys go to the right and I stay with the other two girls. So it happens that I step into someone's house at about 2 AM, I sit down and rest, without being able to sleep until morning comes.

Friday, December 22, 1989

Friday morning: I go to work. I stay only for a few hours, four or five for all I know. Shots can again be heard from the University and helicopters go once again across the sky. I do not know what the army is going to do, especially as, coming to the Law School this morning, I could see the whole avenue 'decorated' with tanks and army forces. In front of Unic Store there were trucks loaded with ammunition and the whole area was heavily guarded. All streets providing access to the Palace Square were blocked with shield-bearing soldiers. All through and around University Square they were working - and obviously have been working round the clock - on cleaning: the streets and sidewalks had been washed clean of blood and all other traces of the previous day, the meeting claims written on walls had been equally erased and, where this had not been possible, they had painted the whole wall in green or grey. The wall of the Intercontinental where we had written 'Do do not work tomorrow!', 'General strike!' was clean and all grey in the morning. But our movement is to go on, our claims are to be rewritten all over the place and even years later the grey wall of the Intercontinental will still bear the 'Down with Communism!' and 'Throw away your cards!' (n. the Communist Party membership cards), in geometric, red letters.

So, there are no traces to be seen on the morning of December 22, 1989 of what there happened the night before. Mother calls at the office, she calls some 5 times in 2 hours. She talks to one of my colleagues, asking her not to let me go downtown again. She is despaired, crying. She calls and let me listen over the phone to the tumult outside, telling me that thousands of people have lined up the streets, going towards Lujerului (n. city limit in NW Bucharest), towards the dairy factory, towards the ICTB (n. a research institute), telling me that helicopters fly really low and they are firing at people protesting. I am so sorry that she too has to see what I have lived through. I cannot promise I am going home; she however asks me to join my colleague that lives in Crângași (n. neighborhood in W Bucharest). At about 11 AM or noon I leave the office and start walking by River Dâmbvița towards Crângași District. Big groups of people with flags - with the Socialist Republic of Romania coat of arms removed - are coming out of their institutions - ICECHIM, Hidrotehnica, Energetica - and walking towards the city centre. When we reach Semănătoarea (n. a big agricultural machinery plant) there is nobody around. It is impressive. There is this corpse on the river shore: a worker covered with a table cloth. I feel so tempted to join the crowds and get back to the centre, but my colleague has promised my mother she will take me home with her and I shall call home from her place. Anyway, we get to her place, I reassure mother and listen dumbfounded to that Decree enforcing the General State of Necessity, forbidding anyone from being in the streets past 11 PM (Ha!), as well as people from gathering in groups of more than 5 (Ha-ha!). Later on, while walking to get some bread, I see this shining, all white helicopter dropping some leaflets typed in big fonts, with a very unexpected text: there are Ceaușescu manifests. I read one of them, where we are told we have been betrayed, that the enemies of the country want to get Transylvania from us and that the road we have picked leads nowhere.

Down at a bookstore somewhat opposite Crângași Market people take out all works reminding one of the man belonging to the past. Three tanks go past down the road and soldiers wave at us, then make the sign of victory to us. People clap their hands at them. They are going to Ciurel Dam, to the dairy factory. Then the first broadcast of the Free Romanian TV gets me at home, watching. At 2 PM I leave, going towards the TV station that is already in the hands of the protesters, joining the crowds of enthusiastic people. Those having one keep a portable radio receiver next to their ears, surrounded by others wanting to learn the latest news. There are various calls being shouted, some of which I know: 'Ceaușescu, have a New Year in a coffin!', 'A new year without a Hero!' (n. Nicolae Ceaușescu was self-proclaimed as Socialist Work Hero). There are announcements that he intends to flee, but the protesters call upon him ironically: 'Ceaușescu, not yet, don't forget to get your ration!' (n. food was rationalized in the 1980s and the main foodstuffs were subject to set rations). I reach the Arch of Triumph and the crowd passes under it, as the army used to do after winning a battle; I go down on my knees, keeping a moment of collectedness for those that are no longer there, those that died fighting, not knowing if they made it or not. We go on and people keep joining us all the time. Someone lifts a stick with a rubber shoe at its top, which paradoxically means that 'The Shoemaker's down!'. There are a lot of people at the TV station, a heterogeneous crowd impossibly to get a comprehensive sight of just as it was yesterday in the University Square. I can but hardly reach the main entrance. There is this Miliția man: a rather fat, pale complexion and black mustache man, so scared that he agrees to be nearly strip-undressed: people take off his belt, the coat of arms on his cap, his cap, his gun. The whole thing is funny and embarrassing, as the man holds his pants and fearfully looks around - just like chased game -, trying to nevertheless smile. I find it a grotesque act, but this is the way people have found to show that their will prevails, that the Miliția too has joined their will.

I cannot not stay there more than a couple of hours, there are too many people, there is too much pressure, so I struggle to leave that swarm, heading towards the city centre. The way towards the Piața Romană is thrilling. There are big barricades being put together in Dorobanți Square, as people move around frantically making do of cars and trucks to reinforce real fortifications; there is word going around of the terrorists that are coming towards the TV station with 3 tanks. We are all told to walk around in small groups. Dozens of TV sets with the sound up at maximum have been turned towards the street, so that people walking around can learn of the latest news. While passing by Lumina Bookstore, I hear for the first time the rumor that tap water was poisoned. 'God, how could they?…' - this is my first thought as I recall the old Middle Age war strategy of throwing poison in wells and setting the crops on fire.

I reach Perla Building. Many, many people out there. Truck loads of merry people, waving the flag with the coat of arms cut off, cars going towards the TV station or in the opposite direction, towards the Palace (n. the Royal Palace). I get to Dorobanți Hotel in the evening and I go to the house I spent the previous night in, to find the lady with only one of her daughters, as the other one, Dacia, has been arrested. The lady is now waiting, quite optimistically, for news. It is about 7 PM - it is dark already - and I start towards Izvor subway station, on my way home, to reassure mother. There are many people in front of the C.C. building. The first free newspaper is being distributed from the balcony of the Universul Building; they've called it 'Libertatea' (En. Freedom).

I have merely been home for half an hour, but I feel I can no longer passively sit watching the TV. There are desperate calls for people to go out in the streets, to gather in ever bigger numbers around strategic points such as the TV station, the Palace Square, the radio station. So I leave home and head downtown. I get off the subway at Izvor, wishing to get to the Palace Square. It is about 9:30 PM and I reach the Brezoianu crossing. Everyone going in the same direction with me has for some reason stopped here. Then I see why: a few tanks are stationed farther up the Gheorghe-Gheorghiu Dej (n. currently the Regina Elisabeta), at the crossing with the Calea Victoriei, in the square between the Romarta Copiilor (n. a store at the time, currently a BRD branch) and the Army House (n. currently the Army Club); their canons up, they are firing towards the Phone Company Building (n. strategic satellite transmitters were located on top of it at the time). Sinister shooting can be heard from Cișmigiu Gardens as well, and firing flares alit the sky above. At a certain moment, the tanks by the Romarta Copiilor turn around and came down towards us, firing right along the avenue we were standing on. We run away and find shelter behind buildings. Most of us then start towards the radio station, up the Nuferilor (n. currently the General Berthelot), as there have been calls for people to go there and defend that point. It is dark, I go on together with the other ones and I cannot say for sure on which side of the building I am. More and more tanks show up, I count 15 of them. Word is spread that they (n. it needs be stated that the impersonal ruled such announcements and rumors many of which later proved to be fake or even purposely fabricated: 'they' were the terrorists, foreign secret service agents, Securitate agents or simply those against the revolution) are shooting at the students down in the Grozăvești campus and many of us start in that direction. Upon the Calea Plevnei - Știrbei Vodă crossing, cars are being searched. I reach the Grozăvești, but it is all quiet, nothing has happened here. I get on this truck, a tipper to be more precise, and it takes us up the river, in front of the student dorms at Regie and all the way to Ciurel Dam, at the very entrance to Dâmbovița water park; there are more trucks here. The whole area is deserted and quiet. So, on top of the same truck we head back downtown, getting off right next to the tanks by the Army House. This small van comes around, supplying the soldiers with bread and yoghurt. I go on and reach the Palace Square.

A terrible night follows. I see the Central University Library (n. formerly the Carol Foundation) burning down, in two stages. Terrorists shoot from the most unexpected locations, usually from the upper floors: from the University Library building, from the Royal Palace, from the apartment building opposite Muzica Store, where I can see fire coming out of the windows, from everywhere, so that we get the feeling we are surrounded. But the protesters never leave the place, incessantly shouting: 'The army is with us!', 'We are not leaving!', 'We are not going home, the dead do not allow it!'. It is all fantastic. All of a sudden, out of a semi-basement window to my right, five men come out and start shooting around them. I do not know what happens to them, I cannot see. I can however see as the cold blood-shot wounded and dead are being carried away, loaded on vans and taken to hospitals. There is a lot of shooting that night - that night also - in the Palace Square; it goes on almost continuously. The Art Museum (n. the National Art Galleries, hosted in the Royal Palace) burns down too, with a lot of black smoke coming out and seeming to perform a mystical, sinister, sepulchral dance on its way to the sky. During a break - if I may call it so - I notice this young man filming and curiously looking around, a sort of astonished satisfaction on his face. He looks like a child that, reading say Andersen's stories, points his hand to the pictures there with the naive desire of stepping in that fairytale scene and he all of a sudden finds himself in there, among those characters, looking around him with an inner, yet controlled happiness, ready at every moment to scream of joy, but not doing so for fear the scream might spoil the reality in his mind. That blond young man's words touch me deeply: he has come from London today with the only purpose of seeing it all with his own eyes. It is his first time in Romania, he is staying at the Intercontinental and will go home only when the fighting ends. A great gesture from this anonymous young Londoner that might very well get killed here, just like many other foreign tourists or reporters.

Saturday, December 23, 1989

It is a hectic night and the dawn comes as a salvation. We encourage ourselves while shouting after the voice of the unseen man calling from inside the TV car: 'Two hours to go!', then 'One hour to go!', then 'Dawn is coming / We're winning!'. Indeed, ours was victory, as we have survived, we are all here and the weak daylight has revived us. I am so cold. I have got neither gloves, nor boots. At around 9:00 AM three white planes go over us; two go first and then, shortly behind them, there follows the third one. I spend the rest of the day in the square. I do not feel like eating, even though trucks bring us hot bread, hundreds of boxes of juice and mineral water. I am not sure if all this time I have had more than half a loaf of bread. I sit down in front of Athénée Palace Hotel (n. currently the Hilton), but I then have to quickly stand up so as not to fall asleep and to embarrass myself in front of the others; thinking of those soldiers, I would be so ashamed to sit here and snooze. Someone notices then that terrorists are shooting from the hotel windows above me. A terror-filled day follows all across town: one can spot someone in a shooting position, firing or ready to fire from the top of various buildings. We once again feel surrounded. The streets look deserted, people find refuge wherever they can, but the military, those uniformed children, remain in position.

I go to Bogdan's place; I need to sit down, nothing else. There is nobody home, so that I sit on the stairs and close my eyes. I can still hear the shooting, as I am close to Dorobanți Hotel. This young woman comes and wakes me up; a beautiful girl, a slice of bread and a cup of hot tea in her hands. She has seen me from her window. It is a gesture that needs no further comment. She takes me upstairs, to her place. Her father is ill, her mother is suffering and only her younger sister, a seventh grade pupil, is more alert. Her name is Cremona and she is a Polytechnic student. They then give me a cup of coffee and let me sit in an armchair and watch the TV. Before 5 PM I leave their place; night is coming. I haven't been able to sleep, but I feel so much better now. At the same time I feel bad I have left the streets for this time, it feels like deserting. I believe I spent 2-3 hours at Cremona's. The block is deserted and when I reach the big crossing I get this feeling snipers are picking up precise targets down the street below and shooting at them from up in Dorobanți Hotel. I run and once again reach the Palace Square. Just as many people, tanks and soldiers. The Royal Palace looks dreadfully, a sinister and painful skeleton is all that remains of the Central University Library; after all, I have witnessed its burning down… Pity! Such a pity! I take it that we Romanians have been punished, maybe even cursed, for otherwise why all this bloodshed? What have we paid for with all these victims, with all these youth brought to a sudden end? Freedom is precious, but why this price in the end of the 20th century?

At a certain moment the crowd get their hands on a terrorist, he has come out of the building across the street from Muzica Store; the rage of the people is boundless, they simply cannot hold themselves. They however try to self-impose a more dignified attitude by joining hands and shouting: 'No violence!', 'We are civilized people!', before going on with: 'Let us see him!', 'Let us see him!'. The man is brought on the balcony and everyone looks with hatred and dander in their eyes at this disfigured head and disheveled hair, at this blood-ridden face. He is scared. He looks horrible. He too is a human being unfortunately, a two-legged being resembling us; physically, he is no different from any of those down the streets and for years and years he walked freely among his menfolk, he worked in this society… An unspeakable work however, once he got the profession of killing, his eyes open, no regrets, no scruples about it. There is something I cannot understand and probably many of us will never understand, a proof that at the beginning we really thought that 'They won't shoot at us! They can't shoot at us!'. What can I say? One can write a lot on it, one can make countless comments on this matter - if it can be called that at all.

Evening comes and I do not know what it is to bring: the recommencement of firing upon us. People notice they are firing from Kretzulescu Church (n. located next to the Royal Palace) and tank cannons are pointed towards the religious building. I shall never forget the hoarse voice of the man in the TV car which begs the soldiers to try hard and aim carefully, so as not to destroy the red brick building. The church is not to be destroyed, but it is to be damaged.

Shortly after 6:00 PM something extraordinary is announced, something we all have been waiting to hear: the illiterate couple which planned all this destruction and for which those two-legged creatures are still out there fighting, oh well, the two former 'honorable children of the people' have been caught up and detained. Where? We do not know. How? We do not know either, but what really matters is that they have not managed to run loose. Should I describe what reaction people have upon learning the news? Some are crying, some are hugging each other, some are simply dumbfounded… Night has fallen. Another shipping of hot bread is made but I am not hungry. I get near the TV car. I am sick and cold. My eyes are closing and I think I can fall asleep while standing. I get on top of this plastic box. To my left, on another plastic box, a young man is standing too. An ambush occurs and we are both pushed off our boxes. That young man helps me get up and from that moment we stay together for the next 18-19 hours. I think I am a bit lucky to meet him, as I feel so sick and I get the shivers. I have no idea what his name is, I only get it he has come straight from his work in or near Ploiești and that he knows nobody in Bucharest. I know nobody around us either, so that his unexpected company is welcome for me. Once this is all over, I unfortunately am not to get any news from him or to learn whether he is still alive or not.

There follows a full night, complete with a lot of shooting. They are shooting from the windows of the Palace, then from the blocks up the Onești (n. currently the Dem I. Dobrescu) that will end like the Central University Library. Terrorists manage to enter the former C.C. building, by using the basement, there is fighting inside, then there is shooting at us again. We find shelter by the entrance to the apartment building across the street, one of the terrorist strongholds, where many apartments burnt the night before. At first there are only the two of us, me and that young man, sitting on the stairs. From above, from the first floor two elder ladies come down: one of them is very old, around 80 and the other one is probably her daughter, around 60. They stay for a while. The older lady then goes up, there is a draught and too much humidity down the hallway. I cannot imagine how they can stay in that apartment, as other apartments in the building are burning, so that the whole first floor is virtually filled with thick smoke. Such a sinister and horrible sight!

Down in the basement water is flowing from the broken pipes. I cannot stay there, I am very cold and I am almost sleeping. So that I once again go in the square, among the others. It is then announced that the terrorists have sent helicopters that are about to arrive and shoot at us. We are urged to enter the building. I feel so bad that I accept, so as to be able to sit down, but I cannot stay for long. I get to this small room, where we are all crammed, without light or fresh air. We can still hear the inferno outside. I do not know why, but the shooting feels much worse when you hear it from inside the building; it all feels more dangerous, more terrible, more frightening, while when you are out and actually see what goes on, it is different, somewhat more appeasing if I may say so. Some 10 minutes later I ask to go out as I feel like fainting. I remain down the hallway together with the young man and we can both see the wounded being carried inside. I however prefer going out in the fresh air. The terrorist helicopters are not but another unconfirmed rumor. But there still is a ceaseless firing upon us. Then there is this old woman, alone in all that stirred crowd; she says she cannot stay inside listening to all those desperate calls on the TV. There is continuous shooting; they are shooting at each other above our very unarmed selves (stubbornness has turned into our only weapon).

Sunday, December 24, 1989

Time passes slowly, we all wait for the dawn, the same dawn that gives us courage. While it is still dark, during a moment of relative calm, we are told to turn off the bonfires, as it seems that the terrorists have set mines about the building. I am shivering, I am so cold. I have not drawn near the bonfire as I cannot stand the thick smoke coming out of it. But I look at those people hurrying to extinguish those pale flames, giving up any hope, any illusion of warming up. I look at them just like a newly born opening up his eyes for the first time and looking at the world, just like the 'Small prince', with naiveté and innocence in his eyes.

I don't know what time it is, maybe it is around 6:00 AM, when the C.C. building is all of a sudden invaded by terrorists. They stand by the windows on the ground and lower floors and point their metal machine-guns towards us. In an extremely short time the whole area is deserted, as we all run behind the tanks. There follows a terrifying pressure, at least as far as I am concerned. There is a tough moment, just like for other people it was tough when hearing about the terrorist helicopters or mined building. Two-three vans come and evacuate the wounded that have been brought out of the building. A sort of bus with broken windows comes next and two young women in white robes get off, offering painkillers. I ask for one and it helps. I am going through a moment of maximum pressure, I do not know what keeps me from bursting into tears, it is maybe my harsh nature keeping me alert and making me feel ashamed about producing such noise like crying. I can see no way out. All that I know next is that I have somehow got to Union Hotel (n. nowadays Union Centre, upon the crossing with the Ion Câmpineanu and not far from the C.C. building). There are not too many of us inside; we sit down or wherever and we all listen to the radio, as well as to the ongoing events outside, for the firing continues. They then start shooting at the entrance to the hotel too, so that we look for a break and run out of the building that has turned insecure. I do not know for how long I have been inside: two hours, four hours, I do not know. Anyway, it is now broad daylight; I run to the C.C. building, as it looks like the safest area, even though it is in the open. The armored window, white building one could not even shoot pictures of before, is once again controlled by the protesters. I am sorry I do not know how they managed to get it back, for the last time I saw it was filled with terrorists. There is less firing now. People are calmer, more relaxed and a few walk down the street leading towards the University Square where candles are ceaselessly being lit. The shooting slowly dies out. The young man I spent the night with says he is going home, as his family knows nothing about him. I feel sorry he is leaving. We part by the entrance to the Faculty of Geography and Geology; I do not have the courage to ask his name. I believe it is around noon, 1:00 PM, 2:00 PM. I am finished. I stay a little longer, looking at people lighting candles, but I do not see anyone crying or sobbing. I once again go towards the Palace Square.

Two terrorists have been caught and people react violently. The two, under 25 years old, neatly dressed, one fair-haired, the other dark-haired, are crouched on a tank, guarded by two-three soldiers. People throw broken glass, sticks, pieces of bread at them. A man takes advantage of soldiers' looking elsewhere and gets up on the tank, hitting hard the blond young man. I look at him and cannot believe this is the way terrorists look like: killing machines, trained human beings, human appearance beings that have chosen the qualified murder of men and women as their profession. I cannot get it… I would so much want to understand how these beings reason, I would like to talk to them, to see how they talk, what they say, how they react, how they gesture etc. etc. etc. I am deeply shaken by this scene and I consent to the furious crowd, but I am intrigued by the condition of such beings, by the fact that such a circumstance ever exists, that such a social category is real, I am intrigued by what the two Molochs together with their species have managed to create… People from all sides shoot pictures of the two. They are eventually led inside the building and, despite the demands of those outside, are not brought out on the 'open stage', meaning on the balcony, again, being first subjected to an interrogation. Shortly afterwards it is announced that four other terrorists have found shelter in Kretzulescu Church and army forces start in that direction. We all wait to see what happens; I stay half an hour more and then I feel about to collapse. It is clear: I cannot keep on. The next thing I know is that I am home, I do not know how this has happened. It is already dark. I do not know what my mother thought when seeing me again in the doorway; it is Sunday night and the last time she heard from me was on Friday. I get undressed and automatically go to bed, almost falling off my feet. I feel sick, but physically I am still in one piece and I think this is all that mattered to my mother. I think that a lot, a hell lot of the survivors of this real war will for a long time be in shock of what they have lived through, will get scared upon hearing a vacuum cleaner and thinking it is a helicopter, hearing someone knocking on the door and thinking they are still shooting etc. etc…

There will be a lot of writing on what happened in Romania during the almost 25 years of progressive terror, as well as between December 14-26, 1989 or afterwards; and I think there should be as much writing about it as there can possibly be.

Anca Moraru, 22 years old

Protocol and Foreign Students Office employee

The Rectorate of the University of Bucharest

Written on December 27-28, 1989

P.S.

Even now, 22 years later, I think there still are unanswered questions. There still are misery, despair, butchered ideals. Now, 22 years later, we ask ourselves whether this was all worth it. Now, 22 years later I know I was not but a dumpling in the great soup of cannon fodder, that people died in vain in that December, that we dreamt and hoped in vain. Romania is degraded and degrading, it has been thrown in misery and poverty, it has been indebted, trivialized, it has been painted in grey. The country has been brought down to a boor, animal state, lacking proper education or medical care, with pensioners and children being mocked at. A corruption, falsehood, humiliation-ridden place where lying has turned into state policy, where useless and illiterate officials live by bantering and abusing the ones they should serve. A place of misty justice, prostituted journalism (for the most part), of extreme dullness and frustration. (December 22, 2011)