Bucharest developed based on the existence of several villages along River Dâmbovița, about half the way between the foothills of the Carpathians and the Danube, in the middle of Vlăsia Woods that slowly gave way to farming land. On the one hand, the city had a somewhat convenient location for traders on their routes from hubs like Istanbul or Piraeus to the North or West, hence the many inns catering for them and the busy streets North of the Old Court where they opened businesses. On the other hand, it was also here that farmers from around the city, but also from a considerable distance, came to sell their produce: cereals from the vast Bărăgan fields, dairy products from South Transylvania or North Wallachia, fish from the many lakes around the city but also from the Danube, fruits from the hills North of Târgoviște, vegetables from the villages starting at the very town limits, tinware from the Gypsy villages to the South-East or rugs from deep in Oltenia.

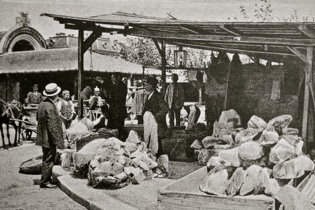

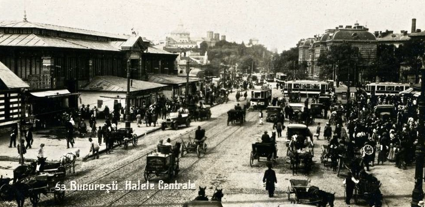

In 1563 the so-called ‘pazar’ (Turkish word coming from the Persian ‘bāzār’) was mentioned for the first time; it was located just off the Court (to the East and North-East of it), in the actual Old Town. It was here that farmers from the neighbouring areas, merchants from afar, as well as different craftsmen came to sell their stuff. Around 1652 the pazar was no longer sufficient for the needs of the town, so a new market opened on the actual site of the National Bank, being called the ‘Pazarul de Sus’ or the ‘Târgul de Sus’ (En. the Upper Market). Approximately the same period saw the founding of the Târgul Moșilor (En. approx. the Fair of the Dead) that was to change location as the town grew, always heading East. As the city later expanded, with new districts developing off what we nowadays call the Old Town, different market places appeared as well. The largest market in the very city centre, the Piața Mare (En. Great Market), later known as the Halele Centrale, developed approximately on the site of the actual Piața Unirii, and it gravitated around the so-called ‘Hala Mare’ (En. The Great Market Hall); while this structure was used mainly for meat products, several other adjacent structures were meant for fruits, vegetables, fish or poultry and there also existed a place for flowers, a bit off than the others. Mid 19th century saw the city relying mainly on two market places in the central area: the above mentioned Piața Mare and the Piața Mică (En. Small Market, later known as Amzei Market) close to the actual Piața Romană. Off the very centre, market places like the Traian or the Matache appeared after 1885, meant to serve the districts they were set in.

At the same time, there were many ambulant street vendors that walked across the city selling products they either bought from markets or produced themselves; this tradition diminished in the first half of the 20th century, but it never died out and even today one can sometimes meet these people in public transport vehicles or near marketplaces and other busy spots. Towards the end of the 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century the ambulant sellers were specialized as well. People from Oltenia (approximately the central part of Wallachia) were into meat, dairy products, poultry, vegetables, while Turks and Bulgarians were selling sweets, peanuts, coffee,

bragă or lemonade in summer, respectively salep in winter. Macedonians and Greeks were offering

cheese or meat pastry,

salt or sesame covrigi, as well as horseradish sausages they had baptized as ‘carnevici’ (‘carne’ standing for ‘meat‘), while Armenians were selling carpets, rugs and coffee grinders. Gypsy men were moving around with carts collecting tin scraps and selling copper or tinware, while the women were selling boiled corn, popcorn and flowers. Jews were trading jewelry, cobs and haberdashery items, some of them settling as exquisite tailors for instance.

The Communist regime tried, just like with everything else, to enforce rules and hence create a stereotype market place, with insipid, metal structures raised in the districts it built overnight across the town. However, the market place remained meant for peasants and farmers coming from the neighbouring countryside. The 1980s however saw a change there, with big, monstrous concrete structures being built to host ‘agricultural and industrial product stores’ and hence to replace the traditional market. The funny thing about them was that, as they were set at the time where there was little - if anything - to buy in shops, their countless counters and shops were empty, hence being called by people ‘the starvation halls’ (Ro. Circul Foamei).

Following the 1989 coup and change of regime, they were overtaken by private businesses and turned into universities (one such structure hosting three universities, just off Timpuri Noi subway station) or malls (a sample lies on Trafic Greu Road, upon its crossing with the Calea Rahovei). The last still standing (and not having its structure altered) such building lies upon the Doamna Ghica - Șoseaua Pantelimon crossing (Piața Delfinului). Here to the left one can see the former such building just behind Unirea Shopping Centre, before it was turned into a mall and saw a total change of structure.

Revived but also facing a tough competition created by often far more conveniently located supermarkets and groceries, traditional markets still exist in Bucharest and they provide good places to explore, with their colourful, vibrant routine. While some turned into small scale malls and the farmers there were replaced by merchants which go to the countryside and bring in the produce to the counter, in other situations you can actually see and meet the people coming to sell their own stuff. It is however the situation of the marketplaces off the city centre, such as the one on the Liviu Rebreanu Street and Camil Ressu, the one on the crossing of the Camil Ressu and the Nicolae Grigorescu or the one on the crossing of the Șoseaua Olteniței and the Șoseaua Berceni. As far as the produce is concerned, there are regional brands to be aware of (with the remark that you do not need to take this fact for granted): Voinești is synonym for good apples, Dăbuleni - for tasty, sweet water melons, Mărginimea Sibiului - for good cow and sheep cheese, Pleșcoi - for those excellent dry mutton sausages, while Covasna County stands for the best potatoes around. Just in case you see these names written somewhere... ;)

Piața Obor. The 17th century saw the founding of the Târgul Moșilor (En. approx. the Fair of the Dead), a fair probably started in order to commemorate the Wallachian soldiers that had died in a battle with the Turks or, according to some researchers, linked with the Roman cult of the dead. The fair used to take place once a year, towards the end of spring, in the Eastern part of the town (at the town limits), changing location as Bucharest grew so as to always be at its limits. It therefore saw different locations such as next to the actual Saints Church (formerly known as Vovidenia Church, located on the Calea Moșilor), Olari Church, Negustori Church, St. Ștefan Church, eventually reaching approximately the actual site of Obor Market, where it was settled for good by Voyevode Grigore Ghica. The street the fair had moved along from the town centre to its limits, called the ‘Podul Târgului din Afară’ (En. ‘the Road of the Outer Market’, in order to make the different from the still existing ‘Târgul Dinlăuntru’ / ‘Inner Market’ in the Old Town) was paved with wood beams and later with cobblestone.

At the same time, the Târgul Moșilor changed tradition: it no longer occurred only once a year, but weekly (occurring on Thursday). For a long while, the death convicted prisoners were brought there, walked around the fair while mounted on a donkey with the conviction hanging from the neck and then executed on site (by hanging or impaling, according to conviction); thieves and merchants caught cheating were just walked around, so that the community saw them and avoided dealing with them from then on. If initially only items linked with the aforementioned cult of the dead were traded at there (pottery, funeral cakes, dishes, wooden water buckets), it soon developed so that almost everything was sold there. In 1903 it doubled as an industrial fair, while 1924 saw the addition of entertainment units such as Montagne russe, the Wheel of Fortune. Around 1935 it ran on a permanent, daily basis, acting both like a fair and like a market. The fair and market had a great importance for the community and not only, as starting with the end of the 18th century, the monarch used to come and open the fair once a week, habit that lasted with interruptions until 1926.

As an important place of the market was taken by the cattle herders and their customers, the interwar period also saw the slow change of name, as the Târgul Moșilor gave way to the Obor (En. cattle market, cattle enclosure). The same period saw the opening of the Halele Obor (En. Obor Market Hall), a Modernist structure built in 1936 following the plans of architects Horia Creangă and Haralamb Georgescu; it is the one pictured above. Later on the fair function was diminished and it eventually died out, the place remaining solely a market place, the largest in the city; the vast variety of produce traded there made it famous among Bucharestians, with pretty much everything on counters, from pieces of furniture, electronics, vegetables or plastics and all the way to poultry. 2007 saw the vast market closed down, in an attempt to make it more efficient and clean it up. On a part of the land resulted a mall is envisaged, while on another stretch a new, 2 floor building was opened in 2010: vegetables are now sold on the ground floor, dairy and meat products - on the floor floor and household stuffs - on the second one; it is pictured here to the left. The architecture of the new building tried to meet, up to a point, that of the interwar Obor Market Hall. The vast market grounds still have something, even though little, resembling the period pictures and drawings of the Târgul Moșilor, with a few entertainment units and a couple of picturesque, vibrant terraces selling

mici, draft wine and beer, turning the whole place into a complete experience. The market place lies off Obor subway station, behind the labyrinth-like Bucur Obor store.

The Halele Centrale. Unfortunately a story of the past, but an important part of the city history, so I simply had to add it here. The Piața Unirii (En. Union Square, with the note that in Romanian the same term, ‘piață’, stands for both a market place and square) was not always a vast empty place as it nowadays is; furthermore, the river that nowadays flows under the ground (with the water you see on the surface being an artificial still water ‘course’) used to flow North of the place, just next to the Hanul lui Manuc. As Bucharest had developed and the ‘târg’ by the Court had long been insufficient, the Piața Mare (En. the Big Market) was set in 1832. The market place developed and starting with 1872 it gravitated around the ‘Hala Mare’ (En. the Great Market Hall), taking as point of reference the Paris Market Halls. Different structures were to be built, each selling specialized products: the Hala Mare was meant mainly for meat products, while other halls were meant for fruits (1883), fish (1887), poultry (1899) and dairy products. The brick wall-surrounded Bibescu Vodă Market to the South-East sold mainly vegetables and was demolished in the 1930s. A slightly more remote market lay to the North-East, behind the Hanul lui Manuc, being meant for flowers only and hosted by a picturesque tin structure raised in 1885 on the site of the former St. Anton Church. The main market place was to be called the Halele Centrale (En. Central Market Halls). The streets around the halls were also filled by many merchants with shops or walking around and the whole area resembled a bazaar. The Flower Market was demolished during the Communist regime (in the 1960s), but its tradition goes on, as it nowadays runs on the crossing of the Calea Rahovei and Uranus streets. The other parts of the Central Market Halls were to be torn down in the 1980s, when the whole area was reshaped according to the

‘systematization’ process. A structure similar (while much smaller) with the Great Market Hall is that of Traian Market which still stands (see below).

Hala Traian. Architect Giulio Magni drew the plans for this hall that opened in 1896. Initially it was called a ‘Market Hall for Trade and a Lamb Slaughter House’. It was later known simply as Traian Market Hall. It was built to cater for the district that developed around it and which reached its peak in the 1900-1940 period. It nowadays hosts a Mega Image Supermarket which is well worth a visit, as one can still see the architectural details inside. The market proper however was moved across the street from the main entrance, in a tin structure. It lies on the crossing of the Calea Traian and Calea Călărașilor and it is on my proposed walk

here.

Hala Matache. The market was also known as by its full name of Matache Măcelaru, with Matache Loloescu starting his butcher’s business towards 1879 and the place slowly developing into a market where many different foodstuffs were traded. The hall here was built of a brick and metal structure, the Southern section being completed in 1887, while the whole building being finished in 1899. The area was buzzing at the time, with extensive residential quarters spreading to the South, but also given the many hotels around the Calea Griviței and the proximity of the main railway station in the city, the Gara de Nord. 1940-1941 saw a restoration of the hall. A scandal occurred in 2010-2011, as the City Hall had a project of creating a wide avenue to make the junction between the Piața Victoriei and the Southern part of the city after passing to the back of the Palace of the Parliament. The project involved the demolishing of several period buildings and the same was supposed to happen to Matache Market Hall. A public protest resulted in a halt of the works, with the proposal of having the building translated 37 m. backwards to make room for the new road. Late March 2013 saw the hall being demolished, with the architecturally valuable structural metal parts being preserved to be employed when the whole thing was rebuilt in the new location as a replica of the original one. At the time this happened, the hall was in a bad state and the street it lay on, the Calea Buzești, was in thorough works, with plenty of rubbish and construction materials around. The market place business moved in a contemporary building to the back. The deadline for the completion of the building in the new location is uncertain, while the works on the new avenue it was razed off to make room for are complete. It lay at a 5 minute walk from Gara de Nord subway station (the picture above was taken in February 2013, before the demolition of the hall).

Piața 1 Mai. Formerly known as Filantropia Market because of the hospital in the vicinity, it spreads from a round, domed corner structure located on the crossing of Ion Mihalache Avenue and Clucerului Street. On the sides facing the two streets meeting here there are pastry and shawarma shops. The market proper lies to the interior, in a metal building hall raised in 1920, of the same architectural structure with that at Matache Hall, the former Central Halls and Traian Hall described above. It is accessible walking for 10-15 minutes from Piața Victoriei subway station or by bus #300 from the same.

When all is said and done, such marketplaces, just like the many merchants crossing the city on their way, had a major contribution to the development of Bucharest. As for the heterogeneous crowd gathering there, that stands for one more proof, if necessary, that the city is alive and kicking. And then, one does not forget very soon the apparently never ending call for customers coming from craftsmen and farmers going there to sell their stuff in the thick smoke coming from a mici grill nearby, with people walking around carrying heavy loads of vegetables while munching on a merdenea:

Mătura, mătura, ia măturaaa! (En. ‘Sweeps, sweeps, sellin’ sweeps!’)

Pește proaspăt, hai să-ți dau pește proaspăt, neamule! (En. ‘Fresh fish, come and get fresh fish, folks!’)

Hai la roșii de grădină, trei lei kilu’, doua kile la cinci lei! (En. ‘Garden tomatoes, 3 lei a kilo, 5 lei for two kilos!’)

_________

Note: all colour pictures by Alexandru Dumitru. Black and white, period pictures are scans of old postcards. If there are copyright issues, please let me know. Thank you.